What do you believe about Grammar?

a. It is best taught in a logical set order, starting from simplest, but teaching full paradigms, fitting topics to the grammar, with a focus on accuracy.

b. It is important but it's not what your course is ordered around from the pupils' point of view. Topics require certain grammar points, although they can often be learned at first as fixed expressions. The complexity is gradually increased, but full paradigms aren't always needed. Grammatical accuracy is part of general accuracy of spelling and recall of structures.

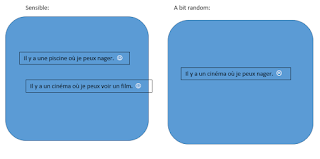

c. Your course has a grammatical core, but it's based on what structures are most powerful in terms of what pupils can do with them. They are structures which can be re-combined to create the pupils' own sentences and they can transfer across topics. Some of the first ones you introduce might be "complex". You won't introduce full paradigms if they aren't necessary for what you want pupils to do.

d. You have a very clear grammatical progression, which is introduced through and integrated into real classroom communication.

e. Your course is built around stories, interesting input, interaction and natural acquisition. Grammatical understanding comes much later and emerges naturally.

What do you believe about Topics?

a. Pupils learn to talk about themselves and their world.

b. Pupils learn about the target language world, culture and Culture.

c. Pupils learn to communicate in practical situations.

d. Stories, clil, projects, real communication with schools abroad.

e. The course isn't organised around topics. Because that's not what they are learning.

What do you believe about Reading and Listening?

a. It is mainly to rehearse and practise the structures that you want pupils to be able to say and write. It is integrated into the lesson developing key structures.

b. Lots of comprehension practice and exam technique, linked to vocabulary, grammar and reading/listening skills. You try to do a little each lesson.

c. Lots of working on strategies to develop pupils' processing skills. Holding language in their head, parsing sentences, accurate phonics, making sense. You might do whole lessons on developing it.

d. Authentic materials, for enjoyment, information and culture.

What do you believe about Communication?

a. Pupils' work is made up of expressions they can recall in order to express themselves. They have set expressions they can use in the classroom. Expressing themselves more freely would produce errors.

b. Pupils' work is to show they can use the grammar and vocabulary they have been learning. They will be able to express themselves once they have learned enough grammar and vocabulary.

c. Pupils can communicate right from the start, including short responses, partial and non verbal responses. It doesn't have to be accurate - they are finding ways to express themselves.

d. Pupils spend a lot of time using the language they are learning, exploring what they can do with it with more and more freedom.

What do you believe about Testing and Assessment?

a. Self testing, low stakes testing and recall activities are key in getting pupils to memorise new language and retain language they already know. If you give pupils a list of 15 words to learn, then the minimum acceptable result is 15/15. With accurate spelling and pronunciation. Tests should test what pupils have been taught.

b. The tasks pupils do should not test specific language points. It's important that they are tasks that require pupils to draw on the entirety of the language they have learned up to this point. This is what makes their evolving language gel and systematise. It lets them work out how it all fits together. Exploring the limits of what they can do is a powerful driver to learn more.

c. Assessments should test what pupils can do with the language they have been learning. Their ability to use it to communicate and develop answers.

d. Assessments are for the teacher and learner to understand how the learning process is progressing.

e. In an assessment, you expect the same standard of work from all pupils. What varies is the level of support individual pupils need in order to achieve that standard.

What do you believe about your Beliefs?

a. You are the Head of Department and it's your job to set a strong vision. Your beliefs are not beliefs, they are evidence-based.

b. Once teachers are in their own classroom, they do their own thing well (or your thing badly). As a department you will determine your team vision. And diversity is a strength not a weakness.

c. It's when you try things you don't "believe in" that you really learn something new.

d. These things aren't important. We just get on with teaching.

So! This is where I ought to be supplying the "key". Can you pin a label on yourself? Can you pin a label on me? Are you clear on what you believe, or are you only too aware of the competing pressures? Let me know in the comments or in a tweet.