One of the things we are reviewing in the light of the Ofsted Research Review is the use of the Target Language for classroom communication.

Of course, the words The Target Language just mean "French" or "Spanish" or whatever language you are studying. And most of the development of pupils speaking "The Target Langauge" happens in the activities of the lessons. For example in pairwork or Speed Spanish activities to build fluency and spontaneity.

But the words "Target Language" have been distorted in the English context. I remember people asking on forums "Can you give me a list of Target Language," meaning set expressions used by the teacher or pupils for routines.

At one point it was the orthodoxy that a "good" lesson had to be conducted by the teacher in the Target Language. Pictures, mime and other physical cues, routines, tone of voice and cognates were all used to make it comprehensible. There were firm believers and quiet heretics. Of course, a lesson in the Target Language wasn't automatically good. And a lesson delivered in English wasn't automatically not good.

But it was axiomatic that exposure to the target language was a good thing. Maybe because of a belief that this led to language acquisition through immersion. The teaching in the mid-1990s had a very strong oral/aural approach, with high energy physical and spoken interactions.

Or maybe it was in order for pupils to make the philosophical conceptual step that this is a real language, used for real communication. A pupil once said to me, "Sir. French people are so clever but so stupid. So clever because they can say everything in French. But so stupid. Why don't they just say it in English." So it is a chance for pupils to understand that their teachers are fluent speakers. We are role models for our language and how to use it. A bit like those amazing clarinet lessons where your teacher spent the first five minutes warming up with some dazzling virtuosic scales.

I remember being told that it was good practice for teachers to use their French to talk to each other in front of pupils. In my experience this leads to very strong antipathy from the pupils who think it is suspicious or rude. Perhaps this is something that we need to make more normal. Or perhaps it is suspicious and rude. Certainly we need to be aware of how it comes across.

In fact, I think this was the major flaw of the whole Target Language approach. It was never explained to pupils, and often it was imposed. I know one of my own children hated French lessons because she was always too hot. To take your blazer off, you had to draw attention to yourself and ask in French. Her teachers would be mortified to know this. But perhaps they should.

If this is starting so sound a little bit as if I was one of the quiet heretics, I should interject here that James Stubbs is one of my heroes. I mentioned here how he programmes his and his pupils' use of the Target Language for classroom communication, not only to keep pace with their progress in the language, but as a driver of progress. He introduces new language, for example tenses, in pupil speak associated with games and activities. James' blog will give you some idea. But if you can get to see him talk, then even better.

I once did an experiment with a class who really enjoyed Spanish. It's the class who were videoed for the OU CDROM lesson. I put a picture on the board as they came in. Several of them commented on it in English. When they sat down, we looked at how many of those things they could actually have said in Spanish. And thought about all the other things they could have said and knew how to say. Then I made them all line up outside and come in again, and each in turn had to say something about the picture. Before the end of the lesson I sent them out again. And changed the picture to a different (but similar) one. This threw most of them because now they wanted to talk about the differences and they wanted to do it in English. But lots of them could say something. At the start of the next lesson I had a picture on the board. They all walked in shielding their eyes, avoiding looking at it and sat down in stony silence.

I would also like to tell you about two students in another class who each had very different approaches. Both went on to study a language at A Level. One is now a doctor and the other trained as a Primary Teacher. In Year 7 I was their form tutor but I didn't teach them Spanish.

One of them would regularly come up to me and talk to me in Spanish. Sometimes spending the whole of break chatting to me. They didn't think of things to say and then try to say them in Spanish. They looked around for things they could say in Spanish and used it as a stream of consciousness we could share in. "Six pupils. Football. Friday today. It's sunny. I like it when it is sunny." Talking for the sake of saying things you can say. A desire to communicate that saw them all the way through to A Level and beyond. Oh. And they also played Resident Evil on their games console swapped to Spanish. Which famously meant they knew the word for "hive" when eventually it came up in an A Level lesson.

The other pupil in the same class would come and ask me for help with verb forms. Or ask me to check the accuracy of some work he was going to hand in. Never spoke a word of Spanish to me. But always asking me questions. Also went on to a top grade at A Level.

So I'm not a hardline believer either way. There's always a way to get the best of both worlds. And the pupils' commitment to it in both cases was key.

So. Some questions to work through with the department:

Do we believe using the Target language for classroom communication is... vital? ... a good thing? ... alienating?

How do we move from fixed routines to more flexible use? Does it keep pace with pupils' progress in the language?

Is it obligatory? Is it so full of fun and joy and purpose that everyone will want to join in? Is it something we can incentivise?

The Ofsted Research Review is concerned with pupils' attitudes to language-learning. So anything which is an alienating obstacle should be removed. They also think that language-learning is about words and grammar and that communication comes later. Personally I am much more an advocate for communication than they seem to be. But I am normally talking about learning to communicate by extending and developing speaking and writing with increasing spontaneity in the lesson activities rather than for classroom communication.

But in their report, Ofsted do still hang on to the idea that there should be use of the Target Language for classroom communication when appropriate. And they want to see this planned so that it keeps pace with progression.

I am not in favour of doing things just because of Ofsted or because we are somehow supposed to. I will continue to advocate for developing pupils' communication as a major part of the lesson activities. I am not sure forced formulaic routine requests are real communication, and if it's alienating or anxiety-inducing then I am not a fan.

I think we will start with routines for teachers and for pupils. And we can work on how the language in the topics of the curriclum

je peux voir mes amis, je dois faire mes devoirs can be translated into the language used in the classroom:

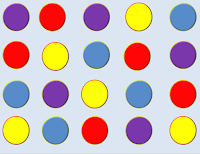

Est-ce que je peux vous montrer une photo de mon chien... Est-ce que je dois écrire la date...And we can bring back the Target Language Connect 4.

It's available here on the Association for Language Learning Speaking Wiki. It is a laminated sheet of coloured circles. When the teacher hears a pupil using the Target Language, they put their name on a circle. (Different coloured circles can be for using the language for different purposes.) When a line is completed, all the pupils on that line get a merit. I last used it when the pupils currently in Year 10 were in Year 7. They used to run to lessons to be the first ones to ask me something in French.

So... We will think about: Continue to develop speaking in the lesson activities and topics. Target language for routines in lessons. Look for ways to integrate the language we learn into more flexible use for classroom communication. Expect and incentivise its use as something rewarding and rewarded.