I have been writing the booklet for the final Unit of Year 9 on Les Loisirs. Overall it's going back to a familiar topic from Year 8 so pupils can deploy their repertoire with fluency and independence. And with a lot more detail. It works on the kind of mini narrative that works so well at GCSE, based on opinions, reasons, if sentences, speech, what was happening, what happened next.

We start with stories about going to the beach, building them up slowly, then transfer the same template to stories about sport, shopping, going to the cinema, skateboarding...

Here is the Key Performance Exemplar for the end of the Unit:

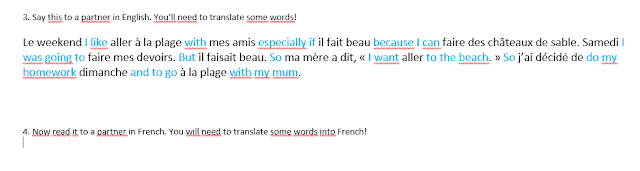

Of course, for Year 9, the booklet has to be carefully scaffolded to make sure all pupils can access it with confidence. And also to make sure that speaking activities with large Year 9 groups happen successfully.

I have taken the usual "Going to the Beach" keep talking sheet and cut it down to introduce it in easy steps. It gradually builds up to its full version through the booklet, adding tenses and narrative by the end of the Unit.

The first activities use listening and speaking, carefully scaffolded with the keep talking grid. It starts with a variation on ski slope writing, here done as a translation. Look closely and you can see that while each sentence offers some scaffolding for the next, there is variation as well as extension.

The ski slope writing is to get pupils familiar with finding what they need on the Keep Talking Sheet and to let the new content integrate with their prior knowledge. It leads directly on to a speaking activity. First as a class, then in pairs.

The picture below is from a powerpoint where the story appears a sentence at a time, and then disappears. With each sentence, the pupils have to remember the story in French from the beginning. Here you can see that the first chunk, "I like to go to the beach" has disappeared completely. The second chunk, "because I can go for a walk" is faintly visible. And the new chunk, "but I don't like to swim" is still visible. This works as a challenge on the board, with pupils enjoying having a go, remembering or making up what they though it said. It recycles familiar language, practising building it into the beginnings of a story.

The ski slope translation and the disappearing story both lead in to the pair work activity. One partner gives a short starter sentence in French. For example, I like to go to the beach. The other partner can add to it or change it: I love to go to the beach because I can swim. They continue, taking turns to add or change the sentence: I love to go to the beach but I don't like to swim.

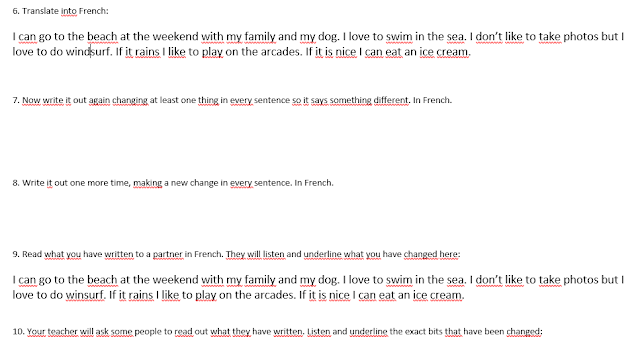

When we move to the next version of the Keep Talking Sheet, with more infinitives and adding talking about the weather, we continue the idea of changing a model sentence. This again starts off as a written task so pupils can find the words they need. Before turning into a task where pupils read their new versions aloud and other pupils have to listen carefully for what has been changed:

This tangled translation (below) is done as a speaking activity. First in English, then in French. Partly to practise recall of the language, but mainly as another opportunity to model how to deploy their French to make a coherent answer which is going to turn into a story:

And this next activity is all about thinking about how to best use the French in order to make something that is coherent.

The teacher reads each of the 3 texts while the pupils are looking at the Keep Talking sheet. The pupils are asked to circle all the infinitives (in the middle column of the sheet) that they hear in each one. They then turn to this page and highlight them in the text. The 3 texts have a similar template in terms of opinions, reason and if sentences. But they are very different in how they handle the content. One of them takes just one infinitive and talks at length but repetitively about playing with a ball. Another has many different infinitives which ends up sounding like an incoherent list of activities. The other has a judiciously chosen set of infinitives which make a coherent story. The class can discuss how well they think each approach works. Then, as you can see in Ex 4, they are given 3 sets of infinitives to create their own 3 versions to try out.

We are only up to page 6 of a 28 page booklet. But you can see the principles emerging:

Using the language of the pupils' core repertoire in a new context.

Integrating Speaking and Listening with Reading and Writing with careful modelling and scaffolding.

Pupils can use the Keep Talking sheet but are challenged to do more and more without it.

Focus on how to create answers with increasing coherence has taken over from a focus on the language.

In a future post we will see another principle:

New language (tenses) is added to the existing repertoire.

With the focus continuing to be on how to deploy it in order to add to what pupils can say. Not for the sake of the language point.

Here's a glimpse of what is to come once we move away from talking about going to the beach: