Disciplinary Literacy is one of the latest terms to be imported in to the school context. You can tell it belongs elsewhere because of the use of the word "discipline" in a very academic sense, not the everyday meaning it has in schools. It means the literacy of the specific school subject. And it's about time we paid attention to it rather than seeing literacy as an extension of the English department somehow foisted on the school. We have entire subjects which are teaching pupils language at least as much as content. In Geography, the subject consists of teaching pupils that their Anglo Saxon words are not good enough. They have to learn the Latinate words. So erosion not wear away. Saltation not bounce down the river. Precipitation not rain and snow. Irrigation not water the crops. I could go on about this at length but I need to get on to MFL.

So in MFL, when we are asked how we pre-teach vocabulary and whether we define the vocabulary pupils are learning, then we can smile and say yes. If we are asked how we make sure that vocabulary is recycled and not lost, and how we make that vocabulary intellectually rich and age appropriate, then we frown and say that's what we are working on. If we are asked when we deliberately programme the teaching of High Frequency Vocabulary, then we get into an argument about fishing and wrestling.

But what if we are asked how we explicitly foreground Technical Vocabulary?

Technical Vocabulary. What would it be? How important would it be? Would it be helpful to test pupils on it explicitly? I have lots of separate ideas and arguments and I need to bring them together, discuss them with everyone else in the department, and decide if we need to change what we do.

There is a social justice argument that we have wrongly neglected explicit grammar teaching. That we assumed pupils who struggle with language-learning need an approach that avoids terminology. And so we are depriving them of the clear building blocks they need. We can also say that pupils appear to love terminology. We know as soon as they put their hand up to answer a grammatical question, they are going to say, "Is it masculine/feminine?" "Is it a cognate?" "Is it a doing word?" These are the 3 most common and perhaps the only explicit grammatical concepts pupils cling on to. And invariably you know they are going to come out with the wrong one for the question you have asked.

So is it worth foregrounding the teaching of grammatical terms? Or is it secondary to an intimate knowledge of the language itself? It is possible to know the terms raven, nightingale, albatross from literature, without being able to identify one in the wild. Just as it is possible to closely observe that little bird with the loud song and sticky up tail in your garden without knowing its name. What makes more sense? To learn lots of names of abstruse (avestruz) birds in the hope one day you see one? Or to see lots of birds and learn their names?

Here are some immediate thoughts that will eventually get pulled together, I promise:

Connectives or Conjunctions?

Conjunctions is a grammatical term. Connectives is an invented term, popularised under the Labour government Literacy Hour drive. It is not a grammatical category. My first instinct is to avoid using "connectives" as non-grammatical and out of use under the current Primary SPAG regime. It includes things like relative pronouns as well as conjunctions. We will come back to this and I may have a surprise.

Modal Verbs?

If you have read any of my posts on our curriculum, you will know the emphasis we put on building pupils' repertoire of language, heavily based around verb + infinitive constructions. Some people call some of these 'Modal Verbs'. Including some teachers in the MFL department and also in some resources used by the English department. The definition they are using is un-grammatical. It's based on a confusion of two ideas. Firstly it is related partly to their function in a sentence - they are followed by an infinitive. So they include can, have to, want to. But they don't include like, love, prefer, going to. Which have exactly the same position in the sentence. Because they use a secondary definition based on a vague idea of meaning - wanting, wishing, probability. This attempt at defining Modal Verbs doesn't delineate a grammatical category. As a definition, it is gaining currency, and I have even seen it transferred into native speaker French grammar definitions. Even though French does not have modal verbs. It's something that English takes from its Germanic roots.

A modal verb is a verb which has no infinitive and is invariable for 3rd person. So can, might, will, would, could, should and must. You can't say "to can" or "he cans" for the verb which means "to be able to."

My instinct is not to use the term Modal Verbs when teaching French. And unlike on Connectives, I don't think I am going to change my mind. We shall see...

Indefinite Articles

I'll talk about Articles. But really they are a proxy for all the other grammatical terms. Definite articles, partitive articles, comparatives, superlatives, possessive pronouns, subject pronouns. Do we need pupils to know the terms? Do we need pupils to know that un/une are indefinite articles? Or 'determiners'? Or do we just need pupils to know that un/une are the French words for a? My instinct is we can give them the label to make the teaching neat and tidy, but what we want is for pupils to understand and use the words un/une correctly.

Let's start to pull some of this together.

Using the example of Indefinite Articles, I am not in favour of SPAG style learning to label things for labelling's sake. Knowing to call something an Indefinite Article is not the point. The point is being able to use the word un/une in a sentence.

Where the technical term is useful in expediting an explanation, a conceptualisation, a distinction and the ability to apply it directly to real language, then we can make use of them. And I think this will be very specific to the grammar which is being learned.

With the case of un/une, we might label this in the booklet as Indefinite Articles, but there is plenty to be dealing with (gender, pronunciation, memorising), without adding terminology to be learned.

So maybe in the case of connectives/conjunctions, I turn out to be in favour of connectives. Because conjunctions is an abstract grammatical category. Whereas connectives is a description of how certain words are deployed, and an invitation to use them in order to improve your expression.

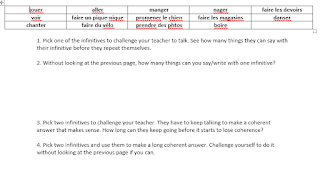

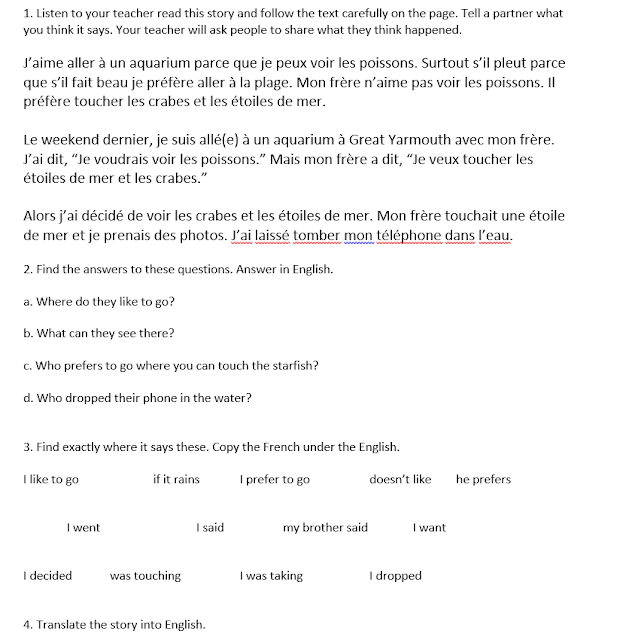

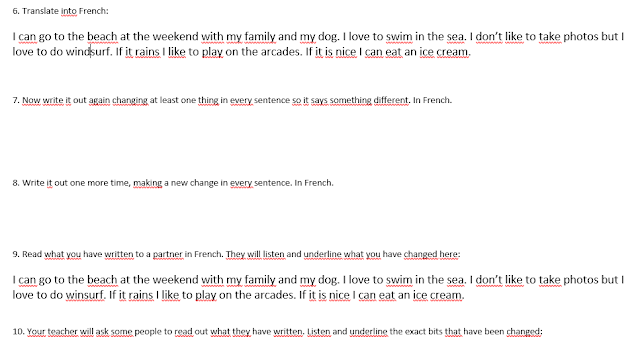

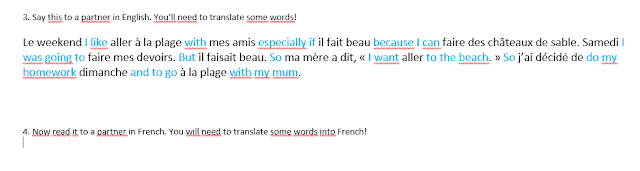

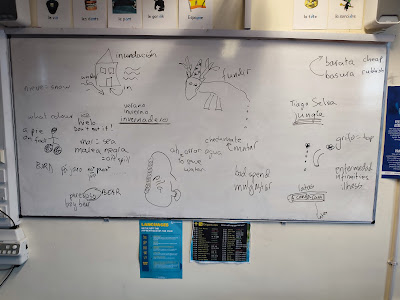

Having a word for can/have to/want to might be useful. But I am not going to stretch to calling them "modal verbs" because French doesn't have modal verbs. In this annotation/highlighting activity (pic below), we don't have a name for them. The best I can do is "verb + infinitive". Which perhaps is enough. Especially when it comes to distinguishing between using a verb in this way, or by conjugating it.

So what terminology is useful? We've discussed this at school, and everyone I spoke to shared the idea that the important terminology is self selecting. Where we need to use it in order for pupils to understand how to deploy their language correctly, then those are the terms we need to highlight and teach explicitly. So there is no need to consider what technical language we "should" be teaching. What is required is that we look at what language we are already using. And make sure we are not assuming that pupils know it without ever explaining it.

So for us, Technical Disciplinary Language means the words we actually use to talk about language. The words we use to guide pupils through the correct selection, formation and deployment of words.

We'll be meeting as a department this week to look at this. My candidates to get us started would be:

verb, infinitive, conjugate, tense, person, regular, irregular, negative

noun, gender, singular, plural

ending, agreement

connective (?!)

These aren't the list of words we "should" be teaching. These are the words we use all the time, perhaps without ever pausing to think if we have checked pupils know what we are taking about.

As always, it brings us back to Scott Thornbury's analogy. It's not about chopping up the cold dead omelette of the language and trying to piece it back together. It's about how you take raw ingredients and cook them into something tasty.