This post is going to start out as a top tip for Dictation. And may end up being just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to what Dictation means for teaching listening in MFL.

It's inspired by @MissWozniak's talk at this weekend's TM MFL Icons Teach Meet. (Recording here.) Listen to Jennifer's talk for ways to start thinking about how to make Dictation accessible, especially in French.

My top tip is, instead of using gapfills, use whole sentences with a word that is changed.

So for example you could give the pupils the sentence with a gap:

J'aime aller à la plage parce que je peux _________ dans la mer.

Then they hear the full sentence J'aime aller à la plage parce que je peux nager dans la mer. And they have to write in the word nager.

I have found it's much easier to give the pupils a full sentence for example:

J'aime aller à la plage parce que je peux jouer dans la mer.

They listen and change jouer to nager.

Our KS3 tests contain this kind of exercise and it is generally done well and with far less panic than you get with a sentence with a gap in it.

I can see two possible reasons for this. Firstly, if you are giving pupils a sentence with a gap, there is already a level of cognitive challenge. The sentence is meant to be there to support them, but with a word missing, they are having to work hard to access the "help". In this case the missing word nager is a key word from the sentence, strong on meaning. Perhaps the first word that they would have been drawn to if they were given the complete sentence to make sense of. We, as experts can make sense of the rest of the sentence without the key word, using meaning and form to deduce what might be missing. This is an exercise in itself for the learner.

Secondly, maybe the tendency is for pupils to focus on the gap. To ignore the rest of the sentence, which as we saw may not be as helpful as it was intended to be. So when they listen, they are focused entirely on the gap in isolation, trying to work out which sounds to fill it with. Which inevitably come and go too quickly, without putting together sound and meaning let alone spelling.

So giving them a whole sentence with one word to be changed means that they have to listen to the whole sentence in order to spot which word is different. And the sentence they are given is a complete sentence that they can start to make sense of. They don't need to try to work out what type of word might go in the gap. They can see jouer and it's then just one step to replacing it with nager.

From experience, I would say it has been quite successful as a way to start asking pupils to transcribe words from dictated text. If you just want a top tip, you could stop here. Because, as I said, this could be just the tip of the iceberg!

What I think this is really getting at is the nature of dictation. It is not a simple exercise in phonic transcription, a friendly test of pupils' grasp of the sound-spelling link.

The Ofsted Research Review is wrong when they say that comprehension of French proceeds in a linear fashion from decoding sounds, to recognising known words and grammar, to arriving at meaning. You cannot tell if the word you heard was port or porc from the sound of the word. You have to have a feedback loop between meaning and sound at the sentence level.

And in French there is a multiplicity of ways of phonetically transcribing any utterance. Some of them meaningful, some of them nonsensical, some grammatically plausible, some not. So dictation is always going to be a test of meaning and grammar as well as the sound-spelling link.

Here's a fun example based on one of the proposed example dictation texts from one of the exam boards: Demain j'ai un concert. This is phonologically indistinguishable from deux mains géants qu'on serre. Of course no pupil is likely to write that. And it contains a grammatical error in the gender of mains. But it shows the wild variation in how an utterance can be interpreted. And makes us question exactly what our pupils are hearing when they listen to French.

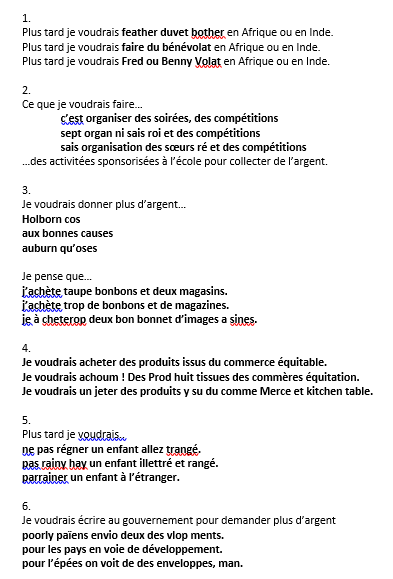

We had a similar thing when we created listening materials to go with some of the recordings that go with the KS3 Expo textbook. Each listening question from the textbook turned into a 4 page set of activities that the pupils did in the computer room, with access to the listening track so they could pause and rewind as required. And we used it with GCSE groups not KS3. In order to make the listenings from the KS3 book accessible to KS4, we needed to structure 4 pages of work per listening track. Because they were not accessible at all. Here's one ridiculous activity that was in there that really makes the point: What are our learners "hearing" when they listen to these tracks?

One of these is inspired by the pupils always hearing huit tissues instead of produits issus. Not to mention what they hear on the listening, again from Expo, about les_expositions!!! Oh, and there's another one where dans la chambre is now universally heard as Donald Trump. Once you've heard it you can't unhear it.

Picking the correct option in each case, is less to do with the sound you hear and much more about making sense of the sound. And turning it into words that make sense as a sentence.

So this isn't really just about dictation. It's about our whole approach to Listening. I think the inclusion of dictation in the new GCSE will be the start of unpicking what happens when we use Listening in the classroom and in the exam.

Firstly, I think dictation will end up not being dictation at all. Because it can't. You can't have an exam which pretends to be a phonics check but which inevitably is much more a check of grammar and meaning. You can't have an exam where there is a near infinite number of correct phonetic renditions of a text. What you will have instead is an exercise where there are sentences read out, but what is really being tested is the spelling of know words. Like nager in the example we began with. So the pupil isn't transcribing, they are recognising the words and being tested on whether they know how to spell it. Or perhaps it's more accurate to say, they are being tested on their ability to spell known words and not attempt to transcribe them because that's where interference from English phonics would lead to error.

Secondly, I think the difficulty of dictation will reveal the difficulty of Listening, as I have sketched out above. The current situation of Listening in the GCSE exams is absurd. I remember being on a panel of mainly Spanish native speaker teachers who thought that our Listening exam level was low. Because we have slow scripted speech and questions in English. It was only when they themselves got some of the questions wrong, they began to realise what was involved. They were used to training pupils to listen to natural speech and answer questions that showed they understood details of what was being said. I have written about it here, but basically they realised that our Listening is not about comprehension but about processing word by word and being tested on specific language features. Not on meaning, but of knowledge of the language. In a kind of dictation that you have to do in your head. A sort of word by word processing is required with a focus on the exact language, which is different to the comprehension of meaning as you listen.

And this will again come back to the error in the Ofsted Research Review. Our learners do not arrive at meaning by processing word by word. They start by approximating overall meaning, content, context. And then proceed to the detail of the language, holding bottom up meaning of words and inflections of words in constant tension with overall top down meaning. The questions in our GCSE target the lowest level of that process: the grasp of the tiniest inflections, sometimes even losing sight of the meaning of the overall sentence. For example the question, "What did one school do that really impressed her?" The answer that shows comprehension would be "They grew fruit and veg on the school field." But this was not an acceptable answer. You had to show word-by-word processing and put "They grew fruit and veg on part of the school field." Can you see how the approach to Listening has lost sight of comprehension of meaning?

I think the difficulties of dictation mean we will have to re-examine what we are doing with listening. On the one hand, where we are expecting word-by-word transcription, it will have to be fairly basic. And it may reveal that listening questions in the past have required mental word-by-word transcription to the extent that they are impossible. Perhaps this revelation may lead to a reconsideration of listening.

No comments:

Post a Comment