Sometimes I can be a bit slow. Eating out in restaurants in Spain with teachers from our exchange school, I often would think, "Gosh, the starter is quite big." Or "Thank goodness the main is quite small." It wasn't until we went over as a family to stay, that my wife said, "Spanish starters are bigger than the mains." And then it all made sense. The same thing happened with the AQA GCSE Reading Exam.

In the 90s and 00s, the Listening and Reading exams didn't need a lot of focus. You worked through the topics and you concentrated on building pupils' repertoire so they could speak and write. The Listening and Reading exams, while containing tricky distractors, were based around testing the language that pupils were learning. So different foods, or numbers, or places in town, or illnesses. At some point this changed. And I missed it.

It might have been around the time we moved from Coursework to Controlled Assessment. When the GCSE that destroyed language learning came in, we were preoccupied with how to preserve teaching pupils how to speak and write spontaneously, when the exam rewarded pre-learned fancy monologues. But while we were grappling with that, there was a change in the Listening and Reading exam that suddenly meant pupils were doing much worse.

I started to notice some things, but it wasn't until the current GCSE came in that I was able to clearly identify them and take them into account in how to prepare for the Listening and Reading exams.

Here are the two main points:

1. The current GCSE has a huge topic vocabulary list in the specification, reflected in the published coursebooks. But the exam boards have wisely ignored most of this vocabulary. Instead, the texts are largely built out of the non topic vocabulary. If this is a new idea to you, click on the link to this previous post to see examples.

2. The Questions in the Listening and Reading exams are not comprehension questions. This previous post gives an explanation, but the most egregious example is the question that asked, "What impressed her about one of the schools?" The honest answer to the question was, "They grew fruit and veg on the school field." But AQA only accepted "They grew fruit and veg on PART OF the school field." Now clearly, the fact that it was part of the field was not the thing that impressed her. But for AQA that was required for the mark. Because AQA questions aren't comprehension questions. They are show you know what all the words mean questions.

And you've probably spotted it. But like with the Spanish starter dishes, it took me a while: The two points above are one and the same. Not only are AQA texts largely based around the non topic words, but these words are also the key to the accepted answer.

So this is what we've been doing with Y11 this week.

Perhaps the usual exam technique would be: Read the questions, locate the answer, answer the question. Instead, we concentrated on identifying Topic and Non Topic vocabulary. This is the version on the projector as we fed back as a whole class. But in the lesson, the pupils had their own printed version. For the first paragraph, I gave them a list of non topic words to find and highlight in yellow: more, then, if, often... In the second paragraph, they are going to be hunting for them for themselves. And they are looking for topic words to highlight in pink.

This led to useful discussion about the importance and difficulty of the pink words and the yellow words. The topic words are often basic words that they know, or are cognates. And where they are unknown, their meaning is often easily deduced from the context. Because they are words strong on "meaning". In a tricky text, the topic words were surprisingly accessible.

The yellow words. For a start there are lots of them. Many of them should be known. But do they get relegated and ignored compared to the topic words? They are often harder to deduce. Because they are more about nuance or the relationships between words in a sentence, rather than referring to concrete meaning. And some of them can have more than one meaning depending on context.

For a comprehension question, the pink words might have been enough. For an AQA answer, you are going to need the yellow words.

Next lesson:

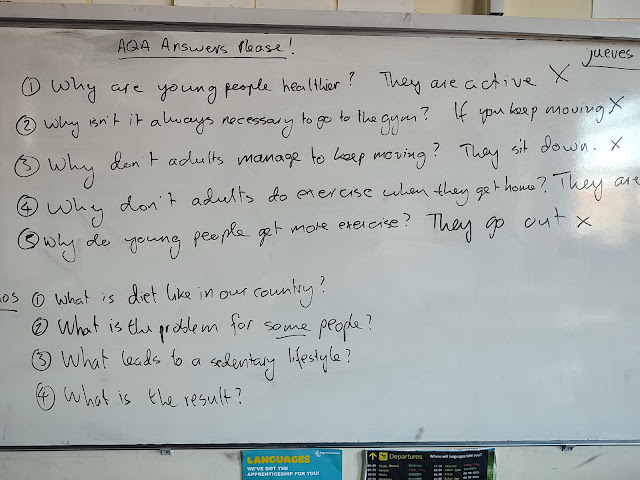

The same text. With questions on the board. And answers on the board too. But while the answers are not wrong, they would not get the mark chez AQA. So for example, "Why are young people healthier?" has the answer, "They are active." Which is correct, but would not be acceptable to AQA. Pupils have to read the text carefully and give the answer, "They are generally more active than older people."

Then you can see the questions for a subsequent paragraph. Here I haven't provided the inAQAdequate answers. It's up to the pupils to make sure their answers reflect what they understand about what AQA require.

I strongly suspect that this will continue with the new GCSE. It's definitely in line with the intentions of the reforms. And the exam boards, if their specifications are accepted, have done a good job of minimising the changes. But once you realise what is going on, it has the potential to change something frustratingly stupid, into an understanding that can help your pupils get more marks!