Where does MFL sit in the current debate about knowledge and skills? We could be the perfect subject to see this play out and explore the rich and fruitful interplay of memory, conceptualisation, accuracy, fluency, expression, and creativity.

There is a lovely idea that skills can be broken down into knowledge. What appears to be a skill is in fact the accumulation and fluent practice of lots of bits of knowledge that can be learned. It's NOT that some people are magically "skillful" or "talented" with some ability that others can't attain. It's that they have learned and practised things that mean their knowledge can be deployed with fluency, confidence and... skill.

It's another way of expressing the idea of "growth mindset." When I was at school, the mindset was one of "talent." Some people were "good" at things and some people just weren't. This became a self-fulfilling prophecy, where a small headstart meant some people went on to excel. And other people gave up or saw themselves as doomed to failure. We've all experienced this narrative of talent (or lack of talent) whether it be in drawing, sport, music, maths, or languages. Growth mindset is the opposite of this. Find out what it is that the "talented" people are doing and practise doing it, in the confidence that you too can learn.

The "skills = knowledge you can learn" argument is currently in vogue, just as people are starting to sneer at the growth mindset. Which is odd. Because it's basically the same idea. I suppose it's a recognition that if we are serious about this, it needs real work and analysis of breaking skills down into micro skills, and won't just happen because of a mindset.

As an amusing aside, we can see how the "knowledge" fad is closely related to other previous fads which are now ridiculed. We used to be exhorted to look at Bloom's taxonomy as a nice pyramid and to beware of only teaching on the lower rungs (memorisation of knowledge) and to try to bring in more "higher order thinking." The knowledge fad is basically the Bloom's pyramid, but this time the exhortation is to spend more time on the lower rungs, working on memorisation. But it's still the same pyramid. It's the use of a neat diagram used to try to pretend teaching is neat and tidy. That knowledge and thinking and creativity can be separated out.

Or the ridiculous "Learning Pyramid" showing that "You remember 5% of what you are told, 10% of what you read..." With its risible 5% increments, its familiar pyramidal structure and again with its neat segregation of learning. Rightly denounced by everyone. Except of course, it's exactly what the knowledge fad is promoting. They've turned it upside down and reversed the percentages so that being lectured is the most important and experiential discovery is the least effective. But it's still the same pyramid with all its neat simplified hierarchy.

And VAK learning styles. Learning styles only makes any sense at all if you are approaching from a knowledge perspective. Pupils self diagnose as weak at reading or auditory processing in a dubious test. Only if the teacher sees learning as the inculcation of important knowledge, would they then swerve those areas of perceived weakness (rather than seeking to develop them), in order to get the knowledge across.

This is because the lovely idea that skills can be broken down into knowledge has been bowdlerised. In fact that's the bowdlerisation right there in that sentence. "Skills can be broken down into knowledge" is only half the deal. The full idea is: Skills can be broken down into knowledge, and that knowledge enables us to successfully and deliberately build up skills. With the second half being the most important: That knowledge enables us to successfully and deliberately build up skills.

And in the toxic mutation that we are seeing, it's that second half which is being neglected.

I will get on to Languages teaching, I promise, and I'm sure you can see that the idea of "knowledge enables us to build up skills" is a perfect fit for what we do.

It goes beyond bowdlerisation. There are toxic mutations. The idea that skills can be broken down into knowledge has been hijacked by the "Knowledge Curriculum" right wing political fad. You hear assertions such as "You can't think without knowledge" advanced to try to separate out memorisation first and thinking maybe later. Knowledge first. Skills... maybe later. Knowledge first, creativity maybe later. The problem with maybe later is that maybe it's always postponed. Clearly this is a problem because it stunts learning and curtails the paradigm of skills broken down into knowledge so it can be built back into skills. I'll come back to this. But first more toxic mutations.

This idea that you can't think, critique, create until a later stage, has been corrupted by the right wing knowledge project in its view of children. There is a philosophy that education is about rescuing children from their ignorance, deplorable communities and degenerate behaviour. There are schools where compliance, conformity, repetition, rote-learning are pushed to exaggerated extremes. Learning is dictated, with an emphasis on authority and "the voices of the best."

The idea that pupils can develop their ability to express themselves, be creative, hear voices like their own, have agency and be empowered, is scorned.

This is all presented as the key to entry into the workforce and escape from deprivation and depravity.

Fortunately this deficit model is limited to a small number of schools. But worryingly, we are in a system of competition and targets where this view of education is incentivised and rewarded and seen as successful.

This political Knowledge Curriculum project likes to hide behind the cognitive science. But it's not the same thing. The Knowledge Curriculum is about what pupils "should be taught." It's political, not educational. And it is not ultimately compatible with the cognitive science. The cognitive science tells us that thinking and memorisation as aspects of learning, cannot be separated.

The mantra of knowledge first, thinking later, is bogus.

We learn by thinking about things. We fit new knowledge into the schemata we already have. Or we alter our schemata in the light of new knowledge. This is fundamental to the "science of learning." It's also born out by what we see. Those pupils who have the confidence to question, to make links, to think of implications, contradictions, associations and even personal leaps of imagination, are the ones who learn best. I'll say it again: the mantra of knowledge first, thinking later, is bogus.

It's the same as the other bogus fads. The Bloom's triangle, the Learning Pyramid. It's a simplistic neat answer by selecting one facet and rejecting the others. Instead of getting stuck in to examine the overlap, the feedback loops, the integration, the reality. It likes to say it's research based. But the "research" is about conforming to a neat model of learning. Not research on the reality of learning. It's an abdication of research. It's reaching for easy clear-cut answers. It is the Nigel Farage of the education debate.

And Languages is a great area to see where the ultimate problem lies.

The foundation of all this mistaken approach, is the way the Knowledge fad sees schemata. The network of knowledge and concepts that pupils are forming. The Knowledge fad thinks that it is transferring the intact conceptual framework along with the knowledge. That well presented diagrams and carefully sequenced teaching will transfer the network of logical links and patterns along with the knowledge. It thinks that the expert who is in possession of a conceptualisation of the whole system, can break it down into neat logical chunks and feed it into the brain of the pupil as if you are programming a robot. (Except we know that even with programming AI robots, you don't do it this way.)

This is familiar territory for us in Languages. This is the Scott Thornbury omelette idea.

Scott Thornbury talks about the synthetic grammar teaching approach that Ofsted were pushing in their "Research Review" and webinars, where someone has chopped up the linguist's overview of the grammar of the language into what seems like logical and organised pieces. He says it is as if you were to show pupils how to create an omelette by taking a cold dead omelette and chopping it into bits. Then you give it to the pupils and ask them to put it back together again. That's not how you make an omelette. You make an omelette from raw ingredients. And you cook them. It's messy, it's different in every case, it's a process.

What if chopping up the Knowledge is not the same as analysing the skills and building them up? What if chopping up the knowledge is just chopping up the knowledge?

So with language learning, it's not the linguist's model of the chopped up grammar that matters. It's what is coalescing in the learner's mind.

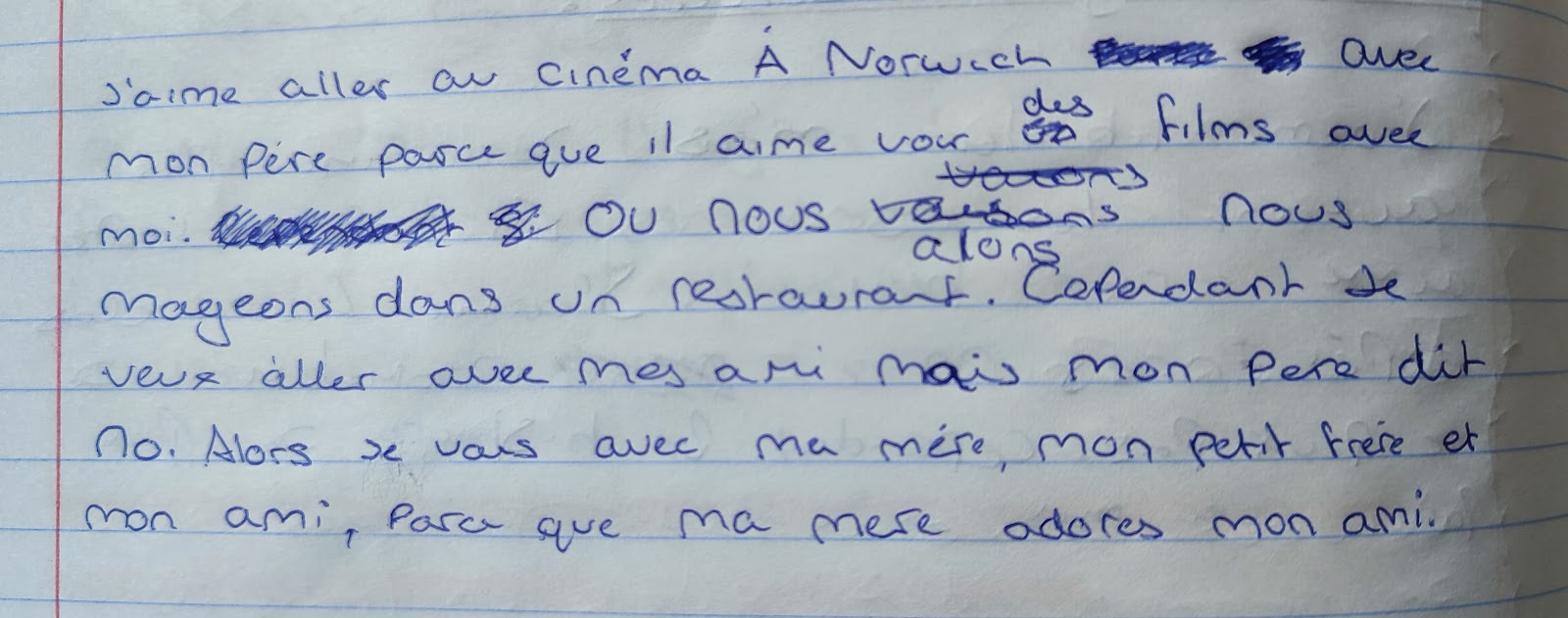

And what is going on in the learner's mind is not neat. Or complete. Pupils' conceptualisation of the language is partial, messy, personal, and includes misconceptions and random associations. It's a process of making patterns, extrapolations and assumptions, making links, (mis)understanding rules. Constantly evolving, and beyond the direct control or conscious knowledge of the teacher or the pupil. And although the teacher may be focused on links between words, the pupil may well be more focused on links between words and the real world. Creating meaning and learning the words for things.

So when we teach the topic of pets, the teacher knows that genders, plurals, pronunciation and the verb to have are most important. But the pupils just want to tell you all their pets and their names. And we wouldn't have it any other way. Once the drive to communicate is lost, language learning doesn't happen.

This is what teaching is. Working with pupils and their evolving understanding. Of course well sequenced planning and clear explanation is important. But the sequencing is the process of growing what the pupil understands and can do. It's not the prearranged sequencing of chopping up the expert's overview into what they imagine should be logical from their position.

Chopping up the Knowledge is not the same as analysing the skills and building them up. Chopping up the knowledge is just chopping up the knowledge.

You're not following a neat foolproof recipe. When you make a roux, your attention is on what's happening in the pan. Stirring, adjusting the heat, adding more liquid as required. Don't keep looking at the recipe or throwing in the amount of liquid it stipulates. Keep your eyes on what's happening in the classroom. That's why having a lovely coloured triangle with percentages or a magic bullet simple pseudo science theory is limited. And what we really should be researching is the reality. How thinking and memory combine. How skills and knowledge inter-relate.

I think I've made my point there. I had some ideas about what that means in my experience of language teaching to include. I will look at them in a later post. I'm running out of space here, but I'll sketch them out because the point of this post is to say it's the reality that matters:

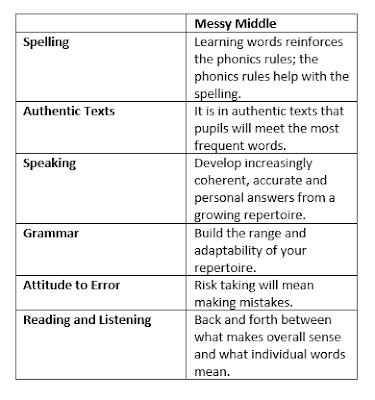

- It's always been my mantra that "It's not about learning more language. It's about getting good at using what you know." This is what ex pupils always identify as the key insight they got from my teaching.

- Try to make pupils' partial stock of language a working repertoire they can deploy. Rather than bits of a plane that will only fly once they eventually have the whole kit.

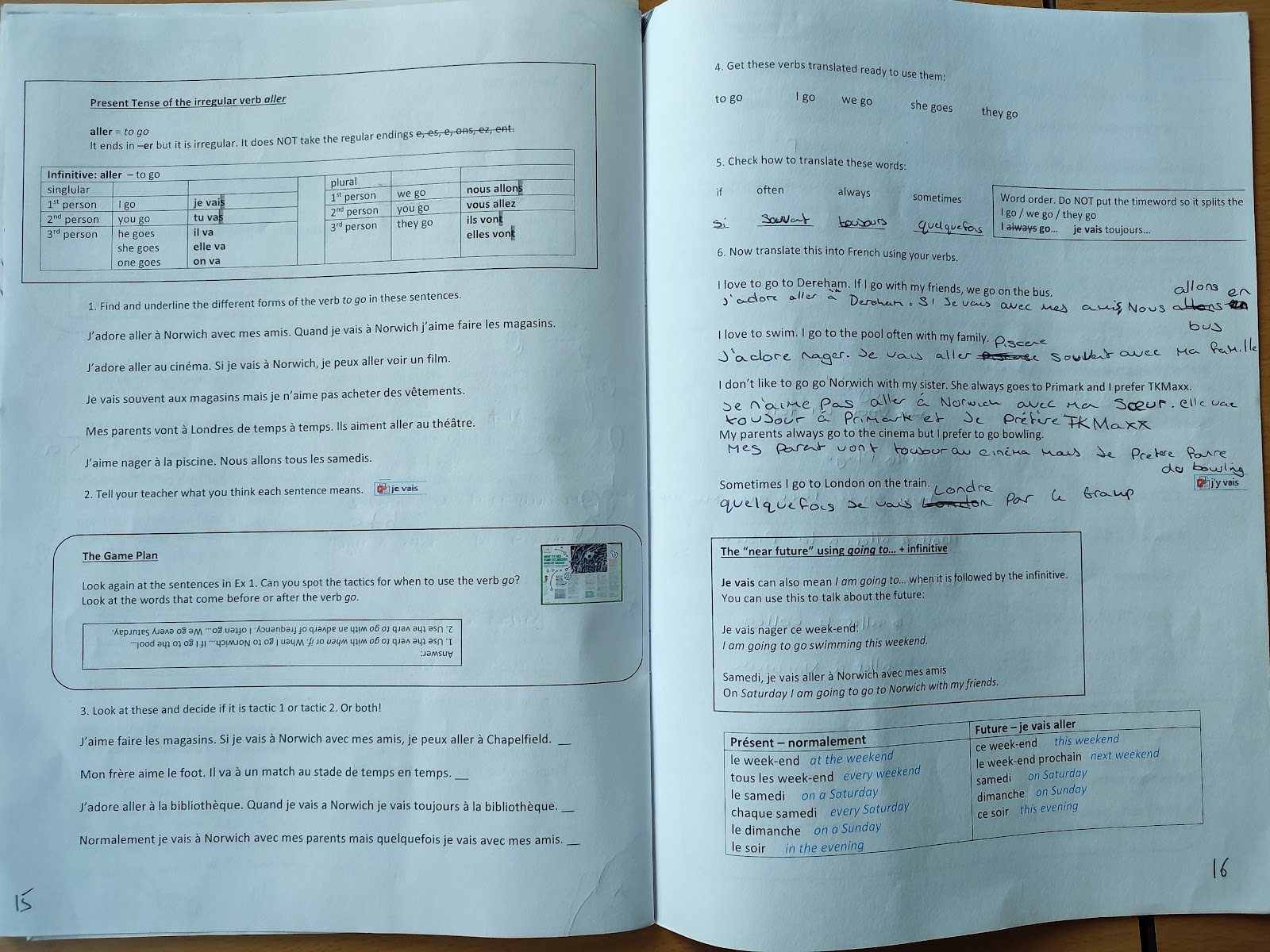

- Define grammar as the kit of language that can be deployed to generate meaning. Not an abstract set of intellectual rules.

- Use metaphor for metacognition so that pupils understand they are accumulating a compact snowball of language. They mustn't let it melt, and more will stick to it.

- Encouraging pupils to use their partial interlanguage to express themselves, understanding that the more they take risks, there will be mistakes. But that's how learning works.

- Understanding that we have to work on thinking up what to say, making it more coherent, more developed, personal, spontaneous. This is as important as learning more language.

- Teaching routines and strategies that pupils can deploy, so that their knowledge is built up into skillful performance and used creatively.

- Constant monitoring of the balance of explicit and inductive conceptualisation and deployment of rules.

- Seeing that it is in using the language that pupils create the links and articulations of their knowledge, explore its limits and possibilities.

If you are familiar with how I teach or with posts on this blog, you will see that this is what I have spent the last 30 years developing. Teaching that engages with where the pupils are. A sequencing of language that creates a living, working repertoire that can be deployed and which will grow.